少し前、日本外国特派員協会の機関紙「NUMBER 1 SHIMBUN」の6月号に石木ダム関連記事が掲載されたとお知らせしました。https://ishikigawa.jp/blog/cat17/2608/

「NUMBER 1 SHIMBUN」の記事はこちらです。http://www.fccj.or.jp/number-1-shimbun/item/946-rebellion-in-the-valley-of-the-fireflies.html

Rebellion in the Valley of the Fireflies

ほたるの里の抵抗

Wednesday, May 31, 2017

In a small village in southern Japan, a dam project has been dividing the local community for over five decades. Most residents have left, but a few households continue the fight against the dam – and they’ve been successful so far.

日本の南の小さな村で、50年以上前のダム計画が地域コミュニティを分断している。住民の多くはここを去ったが、まだいくつかの世帯がダム反対の闘いを続け、その闘いはいまのところ成功している

by Sonja Blaschke

ソニア・ブラシュケ

On a Monday morning in June two years ago, a dozen women gathered in front of a construction site in Koharu Valley in Nagasaki Prefecture. The atmosphere was tense. They hid their faces behind scarves, masks and under wide-brimmed hats with fly nets, and wore long, blue jackets from the local firefly festival to demonstrate their unity. They held signs reading: “We are against the dam” or “Stop forced expropriation.” They had been protesting there almost every single day for several months. What was at stake were their very homes.

Cars pulled up. Several men in work overalls, rubber boots and helmets got out and walked towards the small crowd, which huddled close together. Some of the men worked for a local construction firm, some were Nagasaki prefectural staff.

2年前の6月、月曜の朝、長崎県川原の建設現場の前に数十人の女性が集まっていた。空気ははりつめ、顔をスカーフやマスク、虫除けネットのついたつば広の帽子で隠し、団結を示すための地元のほたる祭りの青いはっぴを着ていた。手に持ったプラカードには、「ダム反対」、「強制収用やめろ」と書かれていた。この場所で、数ヶ月にわたり休みなく毎日反対運動をしている。かれらの故郷の何が危険にさらされているのか。

For over 50 years now, the prefectural government has been trying to build a huge dam – 234 meters wide and 55 meters tall. When completed, the Ishiki Dam would leave what is now the small Kobaru community submerged deep under countless cubic meters of lake water. Disappearing with the town would be its pristine natural surroundings, the habitat of several endemic species, say the protesters.

50年以上にわたり、長崎県は幅234メートル、高さ55メートルの巨大なダムを建設しようと試みてきた。それが完成すると、石木ダムはいまの川原地区を深いダム湖の大量の水の底に沈めることになり、手付かずの自然環境や数種の固有種の生息場所も失われる、と反対者らは言う。

Disappearing with the town would be its pristine natural surroundings, the habitat of several endemic species, say the protesters.

町とともに消えるのは、手付かずの自然環境と数種の固有種の生息場所、と反対者らは言う

Yet, even after all this time, the dam is far from completion; even the foundations have yet to be laid. All that’s visible are a few barriers and some construction machines. The prefecture recently revised the completion date from March 2017 to March 2022.

今でも、ダムは完成には程遠い。その基礎すらも完成してはいない。目に見えるのはいくつかの柵と数機の建設重機。県は最近、建設完了日を2017年3月から2022年3月へと変更した。

Though the officials and construction company managers kept appealing to the women to let the workers pass, the protesters remained silent. “If we start talking, we only get worked up,” Sumiko Iwashita explained later. The women felt that any discussion would lead to offers of compensation, but little in the way of a real exchange of opinions.

行政や建設会社のマネージャーらは女性たちに作業員のために道をあけるよう再三伝えるが、反対者らは沈黙を保つ。「話し始めると、感情的になってしまいます。」と岩下すみ子さんは後に語った。話を始めると、真の意味での意見の交換ではなく補償の提示につながる、と女性らは感じている。

THE AUTHORITIES CONSIDER THE dam necessary to prevent flooding of the nearby Kawatana River and to supply water to the city of Sasebo, located about 40 minutes from Kobaru by car. Some decades ago, the city had experienced a water shortage and had to ration water for a while. However, Kobaru residents find reports about a supposed lack of water in Sasebo exaggerated. They argue that actual water use has been dropping with the introduction of new technology, and a predicted rise in population in Sasebo has failed to materialize. The dam opponents suspect some influence from Tokyo: the Liberal Democratic Party, which has dominated the country for decades, traditionally falls back on infrastructure projects to boost the economy.

行政は、川原から車で40分の場所にある佐世保市に水を供給している近隣の川棚川の氾濫を防ぐにはダムが必要だと考えている。数十年前、佐世保市は水不足を経験し、しばらく水の配給を行わなければならなかったことがある。しかし川原住民は、佐世保市の水が不足するといわれているのは大げさだとする報告を見つけた。その報告では新技術の導入とともに実際の水使用量は減少し続けており、佐世保市人口の増加予想は現実とはなっていない。ダム反対者は政府からの影響を疑っている:日本を数十年にわたり支配してきた自民党は、伝統的に経済対策のためにインフラに頼っている。

Two years on, the protesters have refused to let themselves be intimidated. They are aware that once they give in, the 60 residents that remain in 13 of what were once close to 70 households will have to leave their hometown forever, thereby abandoning land which, in some cases, their ancestors have inhabited for generations. Six days a week, from morning to evening, the women, flanked by non-resident supporters, continue to block access to the site. Most of them are retirees. It once was the men, the household heads, who led the protest, but they were charged with obstruction of construction. If they actively take part in the protest, they can be fined, an activist explained. That was another reason why the women did not want to reveal their identity while protesting.

2年にわたり、抗議者たちは自分たちを鼓舞してきた。ここで降参してしまうと。もともと70世帯が暮らしていたうちの残りの13世帯、60人の住民が故郷を永久に離れなければならなくなり、中には数世代にわたり先祖が住み続けてきた土地を見棄てなければならなくなる。週に6日、朝から夜まで、住民ではない支援者に囲まれダム現場への立ち入りを防ぎ続けている。彼女らの多くは定年退職者である。以前は男性、世帯主が反対運動を指揮していたが、彼らは工事を妨害したことで罪に問われた。反対運動に積極的に参加すれば、罰金を科せられる、と活動家は説明した。こういった理由もあり、女性らは抗議中に身元を明かしたくないと考えている。

It once was the men, the household heads, who led the protest, but they were charged with obstruction of construction.

以前は男性、世帯主が反対運動を指揮していたが、工事を妨害したことで罪に問われた。

“There are not so many of us, so we cannot take turns. That is why we bring our lunches and some water, rain coats and umbrellas,” Iwashita explained. The youthful 66-year-old is one of 60 people who after decades of fighting against the dam continue to live in Kobaru. With her husband and one of her sons she lives in a big house set a little above the fields. “I love nature,” she said with a smile. “Birds always sing here.” People who drive through Kobaru can see big signs reflecting the residents’ attitude on the roadside: “If your hometown was going to disappear – how would you feel?”

「人数がそういるわけでもないので、交代はできません。だから水とお弁当、レインコートと傘を持ってきます。」と岩下さんは言います。若々しい66歳は、ダム建設に何十年も立ち向かいながら川原に住み続けている60人のうちのひとり。ご主人と息子の一人と一緒に、やや高台にある大きな家に住んでいる。「私は自然が好き」、と岩下さんはにっこりと笑います。「ここはいつも鳥が鳴いています。」川原を車で通り抜けると、道沿いに大きな看板があり、それは住民たちの気持ちを代弁している。「あなたの故郷が消えるとしたら、どう思いますか?」

OFFICIALS FROM NAGASAKI PREFECTURE insist they have done much to garner the understanding of the residents. In fact, construction work was paused for 30 years until, in 2009, the authorities decided to make use of the expropriation law, a highly unusual step. Generally, authorities try to “convince” people affected by a construction project, if necessary with pressure – and money, as dam opponents believe.

長崎県職員らは住民の理解を得るためにさまざまなことをしてきた、と強調する。実際のところ、工事は2009年に役人が強制収用法を活用するという非常に珍しい手順を踏むまで30年間休止されていた。一般的に行政は、必要があれば圧力と金銭を使い、建設計画により影響を受ける人々の“説得”をしようとするとダム反対者は信じている。

The protesters took their case to court, but in December 2016 their suit to stop construction was dismissed. Only a few weeks later, on an early Sunday morning in January – the only day of the week on which women did not gather – workers brought heavy machinery to the construction site. Since then, confrontations along the site fence have been resumed with renewed vigour. At the same time, authorities have kept pushing expropriation efforts: for the past three years, a commission has been working on assessing the value of the remaining residents’ land to determine compensation payments.

反対者はこの件を裁判所へと上げたが、2016年12月、建設を止めるための彼らの訴訟は棄却された。そのたった数週間後の1月、女性たちが唯一集まらない日である日曜の早朝、作業者らは重機を建設現場へと運び込んだ。それ以来、新たな心持ちで現場のフェンス沿いでの攻防が再開された。それと同時に、行政は収容に向けた動きを推し進め続けてきた:この3年間、委員会は賠償支払い金額の算定のために、残りの住宅地の価値査定を進めている。

Despite the image of the protesters as being of advanced age, there are also many young people living in Kobaru. One man, 43-year-old Shinya Kawahara, dressed in a striped T-shirt and beige pants, sat in the local community house, its walls decorated with black-and-white photos from protests, handwritten posters and banners from supporters from all over Japan. Born and raised in Kobaru, Kawahara, a shift worker at a local ceramic parts factory, said he could not imagine living elsewhere. He loved playing with his teenage daughters at the river, observing fireflies in early summer, watching birds or collecting bugs. “This is the only home we have. I think it is natural for us to want to protect it.”

反対者は年齢の高い人だという印象があるが、川原には多くの若者も住んでいる。その一人がストライプのTシャツとベージュのパンツを着た43歳のかわはらしんやさんは、抗議活動の白黒写真、日本全国の支援者からの手書きのポスターやバナーの貼られた公民館に座っていた。川原で生まれ育ったかわはらさんは、地元の陶器パーツの工場でシフト勤務をしており、ここ以外に住むことが想像できないという。川で10代の娘と遊んだり、夏の初めには蛍を観察したり、鳥を眺めたり虫を集めることが好きだと言う。「私たちの家はここにしかありません。それを守ろうと思うのは自然なことです。」

He saw policemen lifting grandmothers who were sitting on the ground and hauling them away.

彼は警察が地面に座る祖母たちを持ち上げ、引きずっていくのを見た

He was witness to an event that marked the beginning of this long-running battle of wills. He was 11 in 1982, when he watched officials come to the valley to measure the land in preparation for the dam, accompanied by riot police. He saw policemen lifting grandmothers who were sitting on the ground and hauling them away. Crying children were carried off or thrown to the side, he remembered. Kawahara himself tried to punch a policeman in the stomach, but the man was wearing a metal plate under his shirt.

彼はこの長く続くことになる意思の戦いの始まりとなった出来事の証人でもある。1982年、彼が11歳のとき、ダムの準備に向けた土地の測量のために役人たちが機動隊を連れて来たのを見た。彼は警察が地面に座る祖母たちを持ち上げ、引きずっていくのを見た。泣いている子供たちは連れていかれるか、脇に投げられたのも覚えている。かわはらさんも警察官の腹を殴ろうとしたが、シャツの下には金属のプレートを着込んでいた。

THE REMAINING RESIDENTS POINT to the brutal police operation in 1982 as the reason they lost trust in the prefectural administration. In fact, the authority itself acknowledges that the incident inflicted “deep wounds to the hearts of the residents,” and the governor at the time attempted to make amends by sending apology letters and trying to meet with Kobaru residents.

今も残る住人たちは、1982年のこの残虐な警察の動きを、県政への信頼を失った理由としてあげる。実際、県行政自身がその事件により「住人の心に深い傷」を残したと認めている。また当時の知事は謝罪の手紙を送り、川原の住人に会おうとするなど傷を埋めようと試みている。

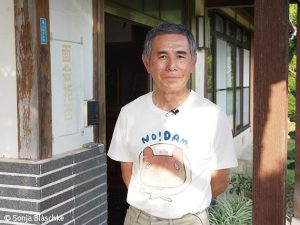

However, four kanji – 面会拒否 – on a sign at the door of 66-year-old Isamu Ishimaru’s house are a token of the failure of those attempts of reconciliation. They read menkai kyohi or “refusal to meet,” and they refer to his deep disappointment in politicians, including the former governor, who broke his promise not to build the dam if just one person was against it.

しかし、石丸勇さん(66歳)の家のドアに貼られた4文字の漢字、面会拒否こそが、和解の試みの失敗の証である。この4文字には、ひとりでも反対の人がいればダムは建設しないと約束した前知事を含む政治家に対する深い失望が現れている。

Although Ishimaru only arrived in 1978 from the nearby Amakusa islands with his parents, he considers the little Kobaru Valley home. “This is where traditional Japanese society still remains intact,” he said. Ishimaru walked slowly on a small road leading up to his house where he lives with his wife and daughter, gazing across the light-green rice fields. Dragonflies were flitting through the air. Between the rice plants one could hear frogs croak.

石丸さんは両親とともに近隣の天草諸島から1978年に川原に来たのだが、川原の里を故郷と考えている。「ここは伝統的な日本社会がまだしっかりと残っているところ。」と石丸さんは妻と娘と住む自宅に向かう小道をゆっくりと歩きながら、時折薄い緑色の田んぼに目をやりながら語った。トンボが空を切る。稲の苗の間からは、かえるの合唱が聞こえる。

“If we start talking, we only get worked up.”

「口を開いたら、熱くなってしまう。」

Ishimaru talked about his defiance while pointing to a small street skirting some of his rice fields. That would be where the new main road would to go through, he explained, as the current one would be submerged. Some of his fields were already expropriated on paper, but he continued to plant rice on them anyway. The former public servant considers the expropriation a violation of the Japanese Constitution, which guarantees the right to life, freedom and pursuit of happiness.

石丸さんは、自身の田んぼに向かう小道を指差しながら果敢な抵抗について語った。もし今の道が水の底に沈むことになれば、その道が通り抜けるメインの道になると彼は説明した。彼の田んぼの一部は、書類上ではすでに収容されたことになっている。しかし彼はそこでの稲作を続けている。元公務員の彼は、収容は生きる権利、自由と幸福の追求を保証する日本国憲法の侵害と考えている。

But there are those who have accepted the government’s plans and moved out. Over the past decades, more than 50 households have given up and left. A new housing estate for those who left the valley stands in nearby Kawatana, the village of 14,000 people of which Kobaru is a part. Although it’s only a few kilometers down the road, the emotional distance is enormous; the people who moved here from Kobaru, especially the elderly generation in their sixties, do not speak with their former neighbors anymore. Both sides feel betrayed.

県の計画を受け入れ、家を出たものもいる。過去数十年の間に、50世帯以上があきらめ、この地を去った。川原を去った人の家屋は今、近隣の川棚という川原も含む人口14,000人の町に建っている。その距離は数キロしかないものの、感情的な距離は非常に遠く、川原から川棚に引っ越した人々、とくに60代の年配の世代は元ご近所さんとは話すこともない。どちらもが、裏切られたと感じている・・・

While there is some support from outside the valley, it seems that most of their immediate neighbors do not feel like getting involved in the struggle. The family of Isshin Taguchi has been living in Kawatana village, downstream from the dam and therefore unaffected by the project, for over a hundred years. In fact, the unaffiliated, conservative local politician and former ministerial bureaucrat who heads up the dam construction committee argues that the dam is important as a measure to prevent floods. In the nineties, part of Kawatana was severely damaged by flooding after strong rainfall. “I am not exactly eager for the dam to be built – but it is just necessary,” he says. Nagasaki Prefecture emphasizes that the Ishiki Dam would protect the area from severe floods that occur with a statistical frequency of once in a hundred years.

川原ではない場所から支援もいくらかあるものの、すぐ近くの隣人たちはこの争いに関りを感じていないように見える。田口一信の家族は川棚町に100年以上住み続けており、ダム下流にあるためダム計画の影響は受けていない。無所属、保守的な地元出身の政治家であり元省職員でダム建設委員会を率いる田口さんは、ダムは洪水を防ぐための大事な方策だと語る。90年代、川棚の一部は強い雨の後の洪水により多大な被害を受けた。「ダムの建設に熱心というわけではない。」と彼は言う。統計的には100年に1度の頻度でおこる重大な洪水から、石木ダムはこの地区を守ることになる、と県は強調する。

Thanks to young, dedicated residents like Shinya Kawahara, there seems to be little chance of the resistance in Kobaru fading.

カワハラシンヤのような若く熱心な住民のおかげで、川原の抵抗行動が尻すぼみになる可能性は小さい

Despite all of the setbacks the Kobaru residents try to stay positive. What encourages them is that the authorities still have not managed to move the project visibly forward. In fact, there are many major construction projects throughout the country, from dams to nuclear power plants, which have been stalled or prevented by local resistance. There was also the local resistance to the Arase Dam in Kumamoto Prefecture that led to its being completely torn down, in the only such case in Japan. Thanks to young, dedicated residents like Shinya Kawahara, who feel called to continue the protest, there seems to be little chance of the resistance in Kobaru fading.

さまざまな障害がありながらも、川原の住民は前向きでいようと心がけている。行政がこのプロジェクトを目に見える形で前進させることができていないことが、彼らを勇気付けている。実際、日本全国にはダムから原子力発電所といった大きな建築計画があるが、地元の抵抗により行き詰まり、回避されたものが多くある。熊本県の荒瀬ダムでも地元の抵抗があり、その結果完全に撤去されることとなった。これは日本で唯一のケースである。若く熱心で、抗議を続けようと声をかけ続けるカワハラシンヤのような住民のおかげで、川原の抵抗行動が尻すぼみになっていく可能性は小さい。

At the protest site, the soft-spoken yet feisty Iwashita revealed how she managed to keep her balance and persevere through the exhausting fight: She did not think ahead much, she said. To relax she likes to rip out weeds in her garden. She emphasized that the women tried to keep up their good spirits by enjoying delicious food and by laughing together a lot, “because you cannot fight if you are depressed.”

反対活動の現場で、口調は柔らかだが気骨のある岩下さんが、疲れる闘いの中どのようにバランスをとりのりこえているのかを話してくれた。あまり先のことは考えないのだ、と彼女は言った。リラックスするのに、庭の雑草を抜くのが好きだと。女性たちの気持ちを明るく保つには、おいしいものを一緒に楽しみ、一緒に笑うことだ、と彼女は強調する。「沈んでいたら闘えないからね。」

Kawahara, the local-born ceramic maker employee, said he suppressed thoughts about the fact that he might have to move away some day. “I will get old in Kobaru,” he stated decisively. ❶

Sonja Blaschke is a freelance East Asia and Australasia correspondent for German print media and a TV producer. She divides her time between Japan and Australia.

地元生まれで陶器メーカー社員のカワハラは、いつかここから引っ越さなければならないかもしれないという思いにふたをしているという。「私は、川原で年をとるのだ」と彼は断固とした口調で語った。

ソニア・ブラシュケはドイツの印刷メディアの東アジア・オーストララジア特派員でTVプロデューサー。日本とオーストラリアの半々で暮らしている。